THE NORMAN CONQUEST

from the

ROMAN DE ROU

TRANSLATED BY EDGAR TAYLOR ESQ. F. S. A.

LONDON,

WILLIAM PICKERING, 1837

This electronic edition

was prepared by

Michael A. Linton, 2004

www.1066.co.nz

TO HUDSON GURNEY, ESQ.

THIS CHRONICLE OF THE NORMAN CONQUEST

IS DEDICATED, IN TESTIMONY OF THE

TRANSLATOR'S RESPECT

AND REGARD.

DETAILED narrative of events so interesting as those which preceded and attended the conquest of England by William, duke of Normandy, needs little apology for its introduction, for the first time, to the english reader. If his feelings are at all in unison with those of the translator, he will welcome the easy access thus afforded to this remarkable chronicle;—by far the most minute, graphic, and animated account of the transactions in question, written by one who lived among the immediate children of the principal actors. The historian will find some value in such a memorial of this great epoch in english affairs;—the genealogist will meet in it some interesting materials applicable to his peculiar pursuits;—and the general reader will hardly fail to take a lively interest in such an illustration of the history of the singular men, who emerged in so short a time from the condition of roving barbarians into that of the conquerors, ennoblers, and munificent adorners of every land in which they settled, and to whom the proudest families of succeeding ages have been eager to trace the honours of their pedigree.

MASTER WACE, the author of the ROMAN DE ROU and chronicle of the dukes of Normandy, from which the ensuing pages are extracted, tells concerning himself, in his prologue, all that is known with any degree of certainty. His name, with several variations of orthography, is not an unusual one in early norman history, though he has not claimed an identification with any known family distinguished by it. The name of Robert, which has been usually assigned to him as an addition, has no sufficient warranty. It certainly occurs in connection with that of Wace in the charters of the abbey of Plessis-Grimoult; (see the Memoires des antiquaires de Norm, viii.); but Richard Wace, a priest whose name occurs in the chartulary of the abbey of St. Sauveur le Vicomte, has been speculated upon by the Abbe dela Rue as having a more probable claim of identification.

In speaking of the numbers which composed William's invading fleet, Wace says,

—jo oi dire a mon pere,

Bien m'en sovint, mais varlet ere;

and it has been in consequence supposed that he intended to represent his father as a cotemporary and even an eye witness of the expedition. It will, however, be easily seen that this is extremely improbable. Wace lived and wrote as late as at least 1173, and could hardly have been born earlier than the commencement of the eleventh century. The assumption that his father was adult in 1066 would give to the latter an improbable age at his son's birth, and a very great one at the time when the 'varlet' could have listened to the tale of his parent's experience. The probability, therefore, is, that Wace only meant to refer to his father as a suitable authority, conveying information which he might easily have derived from living among those who actually shared in the expedition. It is clear, however, that in another place, p. 115, he directly asserts his own communication with persons adult at the conquest; for, in speaking of the comet that preceded it, he refers to the report of eye-witnesses as his personal authority:

Asez vi homes ki la virent,

Ki ainz e poiz lunges veskirent.

Master Wace tells us that he was born in Jersey;—probably soon after 1100. He was taken young to be educated at Caen, and proceeded thence to the proper dominions of the king of France; returning eventually to Caen, where he betook himself to writing 'romanz.' He says that he finished his 'Roman de Brut' (now in course of publication at Rouen) in 1155; and that he lived under three Henries; namely Henry I. and II. of England, and the latter's son Henry, who died young. His principal patron was Henry II. who gave him a prebend of the cathedral of Bayeux. It appears, we are told, from the archives oi that church, that he held the office nineteen years. We learn from him, however, that he did not consider his reward equal to his desert; and he dwells on further promises, which would have been more acceptable if followed by performance.

His chronicle (which he says he wrote in 1160) continues down to 1106; and ends in apparent ill humour at Benoit de Sainte-More's being employed upon a similar task. His concluding words are,

Ci faut li livre maistre Wace,

Qu'in velt avant fere—s'in face!

He is reported to have died in England as late as 1184. He certainly wrote after 1173, for his ascending chronicle of the dukes of Normandy speaks of events which occurred in that year.

The earlier portions of his chronicle, like the pages of Ordericus Vitalis, teem with wonders. His principal sources of these materials were Dudo de St. Quintin, and William of Jumieges. But, as M. Guizot observes in vindication of the latter, the reproach is certainly not, that having truth and error within his reach he selected the latter, but that with no choice about the matter he used the only materials that were in his power. When he reached the era of the conqueror, more complete and authentic information was within his reach; and the perusal of this later portion of his work will perhaps leave no unfavorable impression as to the judgment and fidelity with which he has used his materials, especially with regard to the narrative of the great english expedition. There is an obvious desire to represent the truth, and to state the doubt when certainty was not attainable; and it may not escape the reader, that though Wace is far from wanting in poetic spirit, he sometimes rejects precisely those ornaments of his story which were most attractive for a poet's purpose, and for the use of which grave example might be pleaded.

He is particularly interesting whenever his subject leads to local description applicable to his more immediate neighbourhood. From that part of Normandy in particular his list of the chiefs present at the battle of Hastings has its principal materials, The allusions, in which he abounds, to the personal history and conduct of many of these leaders give great value to this portion of his chronicle. Anachronisms no doubt are easily to be discovered, from which none of the chroniclers of the day were or could be expected to be exempt. His Christian names are sometimes incorrect; an error which he certainly might have avoided had he followed the safer policy of Brompton, who covers his inability to enter upon that branch of his work, by roundly asserting that truth was unattainable.

If Wace is followed on the map, it will readily be seen to what extent the fiefs in his own district of Normandy predominate in his catalogue. He even commemorates the communes of neigh- bouring towns; and the arrangement throughout is determined by circumstances of propinquity, by rhyme, or other casual association. But with all the drawbacks which may be claimed, W ace's roll, partial and confined in extent as it is, must always be considered an interesting and valuable document. Even if it be taken as the mere gossip and tradition of the neighbourhood, it belongs to a period so little removed from that of the immediate actors, that it cannot be read with indifference. It bears a character of general probability in the main, of simplicity and of absence of any purpose of deception. It puts together much local and family information, gathered by an intelligent associate of those whose means of knowledge was recent and direct; and it may be read, so far as it goes, with far less distrust, and is in fact supported by more external authority both positive and negative, than those lists which were once of high pretension, but are now universally abandoned as fabricated or corrupt.[2]

The narrative of the english expedition is the main object of the present volume: but it seemed desirable to prefix the leading passages of William's early history; not only for the purpose of introducing many of the persons with whom the reader is afterwards to become better acquainted, but with the view of exhibiting a lively picture of the difficulties attending William's opening career—of the energy with which he triumphed over his enemies, and directed his turbulent subjects to useful purposes—and of the hazards he incurred, in attempting so bold an expedition in the presence of such dangerous neighbours. The narratives of the revolt quelled at Valdesdunes, and of the affairs of Arques, Mortemer, and Varaville, are among the most picturesque and graphic portions of Wace's chronicle, and derive much interest from their bearing upon local history and description.

The division into chapters, it may be proper to observe, is a liberty taken with the original by the translator; and his further liberties are those of omitting portions of the duke's early adventures, and of restoring, in one or two cases, the proper chronological arrangement, which Wace does not always observe.

It may be asked, why the version is prose? The answer may be, that the translator's wish was to place before the english reader a literal narrative, and not to attempt the representation of a poetical curiosity; if conscious of the power of so doing, to which however he makes no pretension. To those, who wish to judge of the style and diction of the original chronicle, it is easily accessible in the Rouen edition; and occasional extracts will be given, which may answer the purpose of most readers. It was considered to be an idle attempt to pretend to represent such a work in modern english verse. In so doing, the fidelity of the narrative must have been more or less sacrificed, especially if rhyme had been attempted; and without rhyme there could hardly have been much resemblance.

The object in view has been to represent the author's narrative simply and correctly; but the printed text is obviously inaccurate, and its want of precision in grammar often creates difficulty in translation. The lapse of words, and even of lines, defects in the rhymes, and other circumstances noticed in M. Raynouard's observations, betray the inaccuracy of the MS. from which it was taken. Nevertheless, this MS.—the one of the British Museum, MS. Reg. 4. C. xi.,—appears to be, on the whole, the best of the existing transcripts. It is of the date of about 1200; its style is anglicized, the grammar loose, and parts of it are lost. It has one peculiar interest, that of having belonged to the library of Battle abbey, for which it was no doubt made; it bears the inscription, 'LIBER ABBATIAE SANCTl MARTINI DE BELLO.'

The plan and extent of this volume did not admit of discussions concerning the many disputed historical questions as to the respective rights, wrongs, pretensions or grievances of the great rivals, whose fates were decided by the expedition. Abundant materials are now open for the english reader's judgment, in the historical works adapted to such inquiries. Wace's account, published at a norman court, and under the patronage of the conqueror's family, may be expected to represent the leading facts in a light favourable to norman pretensions; but on the whole, the impression left on a perusal of his report will probably be, that it is fair, and creditable to the author's general judgment and fidelity as an historian.

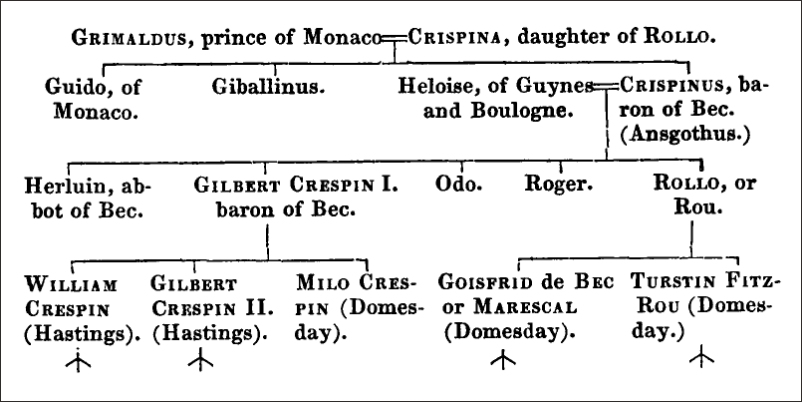

Notes are appended to the text, directed mainly to local and genealogical illustrations, and particularly to that species of information which is, in a great degree, new to the english reader,—the pointing out the cradles of great norman families, whose representatives are stated to have been present at the expedition. Much of the material for this purpose was supplied in the truly valuable and interesting notes to the Rouen edition, written by M. Auguste Le Prevost, a resident antiquary of great and deserved reputation, who has also obliged the translator by additional illustrations in MS. Further information has been sought in various other quarters. The translator's wish has been to keep the branch of his work within reasonable limits; though the result may after all be, that he will be thought too diffuse on these points for the general reader, and too brief for the satisfaction of those whose pursuits lie in the direction of such inquiries. Wherever notes, borrowed substantially from M. Le Prevost, may be considered as turning on his personal or local information, his authority is cited by adding his initials, A.L.P. It was believed that all were likely to attach importance on doubtful subjects to the testimony or opinion of an active and intelligent local inquirer. But, on the other hand, the translator has not scrupled on all occasions to use his own judgment, and the assistance derived from other sources; and these have sometimes led him to different conclusions from those of his predecessors. He has particularly to acknowledge his great obligations to Mr. Stapleton, for supervision of his notes on chapters 22 and 23. Those who know the extent and accuracy of that gentleman's acquaintance with these subjects, will appreciate the great value of his assistance.

In the notes on those chapters, the translator's design has mainly been to trace the locality of the fiefs in question, and to refer to other evidence, such as that of Domesday, with regard to each holder's share in the expedition; adding, where it could be done, the state and ownership of such fiefs at the time of the compilation of the roll of Hen. II. copied into the Red book of our exchequer. The english history of these families has not been dwelt upon. Those who wish to follow up that branch of the subject, can at once refer to Dugdale's Baronage, and other authorities easily accessible. In the references to Domesday book, the obviously convenient method has been to have recourse to the very useful Introduction to that record, published in 1833, under the direction of the Record-commissioners.

In the orthography of the proper names, that of Wace has been strictly observed in the translator's text; his notes generally giving what is conceived to be the proper or more modern version of each. The necessity for this precaution is abundantly shown by the confusion and mistakes that have arisen from modernizing names, (of the true relation or derivation of which a translator is sometimes scantily informed,) without supplying at the same time the opportunity of correction, by a faithful quotation of the original. The translator here begs to express his fear lest he has in one respect violated his own rule, by the use he has made of FITZ as a prefix. It is right the reader should bear in mind, that throughout the original the term used is filz,—such as 'le filz Osber de Bretuil,' &c.; and it might have been better, by a literal translation, to have avoided the appearance of an anachronous use of the patronymic form afterwards so common.

The proper completion of the notes would consist in tracing the identity and possession of the fiefs, from the Red book roll of the exchequer downwards, to the lists formed, after the general confiscation of the estates of king John's adherents, by Philip Augustus. The translator has only had access to the former, as to which a few words may be said. It is a beautiful transcript from a roll, a portion of which still exists, according to the report of Mr. Stapleton, in the Hotel Soubise at Paris. Ducarel has printed, though very incorrectly, a transcript from our exchequer record.[3] The roll itself was probably completed between the twentieth and thirtieth years of Hen. II.; but that part of it which relates to the fees of the cathedral church of Bayeux is an abstract of an inquest of an earlier date, namely, of about 1133, taken on the death of Richard Fitz- Samson the bishop, and lately printed in the 8th vol. of the 'Memoires des antiquaires de Normandie,' This circumstance creates anachronisms in the roll, that are still more apparent in the one published—also incorrectly—in Duchesne's Scriptores, from a MS. now in the King's library at Paris. The roll of Hen. II. is only the basis of Duchesne's; which was obviously compiled after the confiscations of Philip Augustus; to whose era, and the then existing state of things, the entries are made to conform. Some who have not examined into the minutiae of these records, have supposed that the list, with which they close, of men who neither appeared nor made any return, refers to those who adhered to John; instead of its being, as the fact is, a mere record of defaulters under Hen. II.

There are historical traces of attempts under that monarch, to form a sort of norman Domesday, for purposes, no doubt, of revenue. It would seem that this design was resisted, and perhaps was only imperfectly executed in the form we find the existing roll. Philip Augustus afterwards caused much more complete registers of the Foeda Normannorum to be formed. Transcripts of these are in the King's library, and at the Hotel Soubise, and partially in the Liber-niger of Coutances which M. de Gerville quotes. The 'Fceda Normannorum' in Duchesne seems part of a document of this later period.

While this volume was in progress, and after the notes had been prepared, the 7th and 8th vols. of the 'Memoires des antiquaires de Normandie' reached the translator. They contain a calendar and analysis of a vast number of charters to religious houses within the department of Calvados, and furnish a perpetual recurrence of the names of the early owners of the principal fiefs in that district.

Another great addition has at the same time been made to the stock of materials for the illustration of Wace, in the publication at Rouen of the first vol. of the 'Chroniques Anglo-Normandes,' comprising such portions of Gaimar, of the Estoire de Seint AEdward le Rei, of the continuation of Wace's Brut d'Angleterre, and of Benoit de Sainte-More, as relate to the norman conquest. They had all been previously resorted to in MS. and more copious extracts would have been added, if they had not been made so accessible by the publication referred to. Its continuation will add other valuable historic documents relative to the period in question.

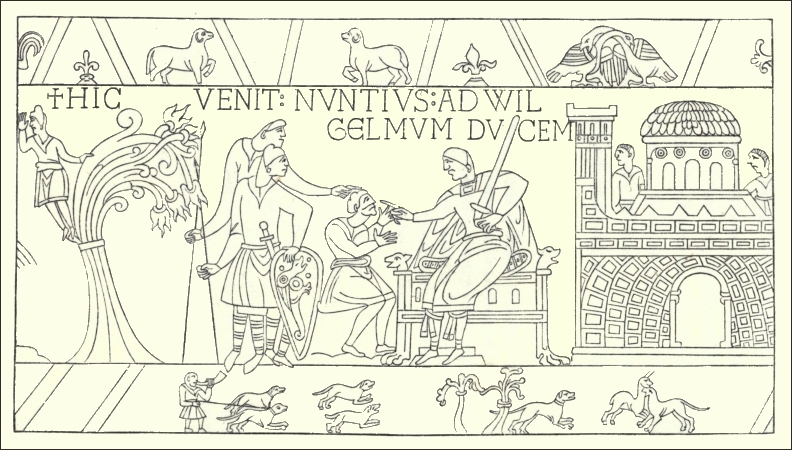

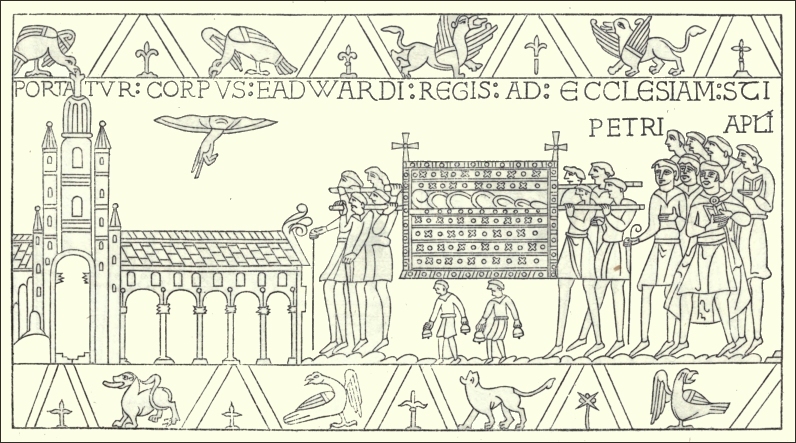

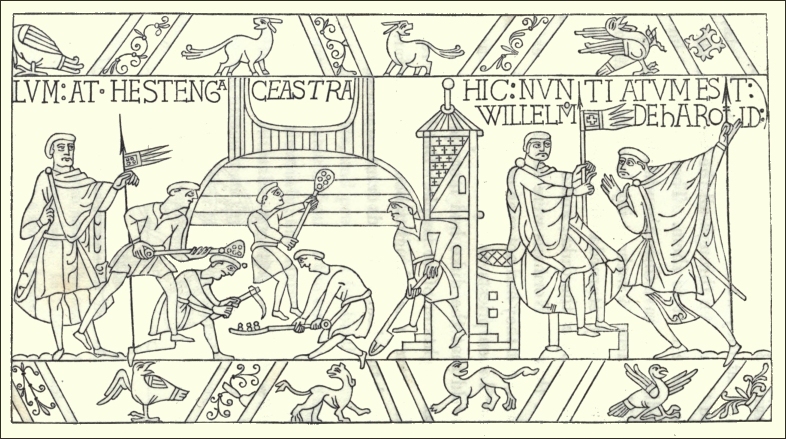

For the graphic illustrations of the volume recourse has been had to a few of the illuminations of the beautiful Cambridge MS. of the Estoire de Seint .ZEdward le Rei. Several other subjects, that appeared appropriate, have been added from various sources. But the principal storehouse of the illustrations has been that noble and exquisite relic of antiquity, the tapestry of the cathedral of Bayeux. To this series of pictures the chronicle of Wace, (a prebend of that church, as already observed,) would almost seem to have been intended as what, in modern times, would be called the letter press. The controversies long carried on, as to the age of this interesting piece of workmanship, and as to the identity of the Matilda to whom it may owe its origin, need not be reviewed here. The reader will find in Ducarel, in the observations of M. H. F. Delauney annexed to the French translation of Ducarel, in the Archseologia, in Mr. Dawson Turner's Letters, Dr. Dibdin's Tour, and other modern works, ingenious and ample discussions upon what is known or conjectured on the subject.

Speculations have been hazarded, with the view of testing the era of the tapestry by Wace's supposed want of agreement with the story of the former. It seems assumed that this variance would not have occurred, had the tapestry been in existence when he wrote. It is not clear, however, that there is any material variance; but if there be, it is surely somewhat hasty to assume on that account, either that Wace preceded, or that he was unacquainted with the worsted chronicle. He obviously sought his authorities in various quarters; and he might very well have known and rejected the testimony of the tapestry, on any matter of fact regarding which there were conflicting accounts. It is very curious that two such monuments of antiquity should be connected with the same church; but it is left to others to speculate whether this was accidental, or what influence, if any, the work of either party had on that of the other.

Lastly, a small map of Normandy has been added, for the illustration of Wace's work and of the accompanying notes. With the exception of the leading monastic establishments, (which were considered a convenient addition, though many of them were founded at a later period), little is shown upon the map beyond the towns and fiefs introduced by Wace; and these are laid down so far as the means of knowledge or probable conjecture presented themselves. In the execution of this little map, no pretension is made to strict geographical or even chronological accuracy; neither has uniformity been preserved in the language of the names; but such as it is, it will probably be found sufficiently full and precise to answer the general purpose for which it is designed.

PROLOGUE CONCERNING THE AUTHOR OF THIS BOOK,

SETTING FORTH HIS INTENT AND DEGREE.

TO commemorate the deeds, the sayings, and manners of our ancestors, to tell the felonies of felons and the baronage of barons[4] , men should read aloud at feasts the gests and histories of other times; and therefore they did well, and should be highly prized and rewarded who first wrote books, and recorded therein concerning the noble deeds and good words which the barons and lords did and said in days of old. Long since would those things have been forgotten, were it not that the tale thereof has been told, and their history duly recorded and put in remembrance.

Many a city hath once been, and many a noble state, whereof we should now have known nothing; and many a deed has been done of old, which would have passed away, if such things had not been written down, and read and rehearsed by clerks.

The fame of Thebes was great, and Babylon had once a mighty name; Troy also was of great power, and Nineveh was a city broad and long; but whoso should now seek them would scarce find their place.

Nebuchadnezzar was a great king; he made an image of gold, sixty cubits in height, and six cubits in breadth; but he who should seek ever so carefully would not, I ween, find out where his bones were laid: yet thanks to the good clerks, who have written for us in books the tales of times past, we know and can recount the marvellous works done in the days that are gone by.

Alexander was a mighty king; he conquered twelve kingdoms in twelve years: he had many lands and much wealth, and was a king of great power; but his conquests availed him little, he was poisoned and died. Caesar, whose deeds were so many and bold, who conquered and possessed more of the world than any man before or since could do, was at last, as we read, slain by treason, and fell in the capitol. Both these mighty men, the lords of so many lands, who vanquished so many kings, after their deaths held of all their possessions nought but their bodies' length. What availed them, or how are they the better for their rich booty and wide conquests? It is only from what they have read, that men learn that Alexander and Csesar were. Their names have endured many years; yet they would have been utterly forgotten long ago, if their story had not been written down.

All things hasten to decay; all fall; all perish; all come to an end. Man dieth, iron consumeth, wood decayeth; towers crumble, strong walls fall down, the rose withereth away; the war-horse waxeth feeble, gay trappings grow old; all the works of men's hands perish.[5] Thus we are taught that all die, both clerk and lay; and short would be the fame of any after death, if their history did not endure by being written in the book of the clerk.

The story of the Normans is long and hard to put into romanz. If any one ask who it is that tells it and writes this history, let him know that I am Wace, of the isle of Jersey, which is in the western sea, appendant to the fief of Normandy. I was born in the island of Jersey, but was taken to Caen when young; and, being there taught, went afterwards to France, where I remained for a long time. When I returned thence, I dwelt long at Caen, and there turned myself to making romances, of which I wrote many.

In former times, they who wrote gests and his- tories of other days used to be beloved, and much prized and honoured. They had rich gifts from the barons and noble ladies; but now I may pon- der long, and write and translate books, and may make many a romance and sirvente, ere I find any one, how courteous soever he may be, who will do me any honour, or give me enough even to pay a scribe. I talk to rich men who have rents and money; it is for them that the book is made, that the tale well told and written down; but noblesse now is dead, and largesse hath perished with it[6]; so that I have found none, let me travel where I will, who will bestow ought upon me, save king Henry the second. He gave me, so God reward him, a prebend at Bayeux[7] , and many other good gifts. He was grandson of the first king Henry, and father of the third[8] . Three kings—dukes and kings—dukes of Normandy, and kings of England—all three have I known, being a readingclerk in their days.

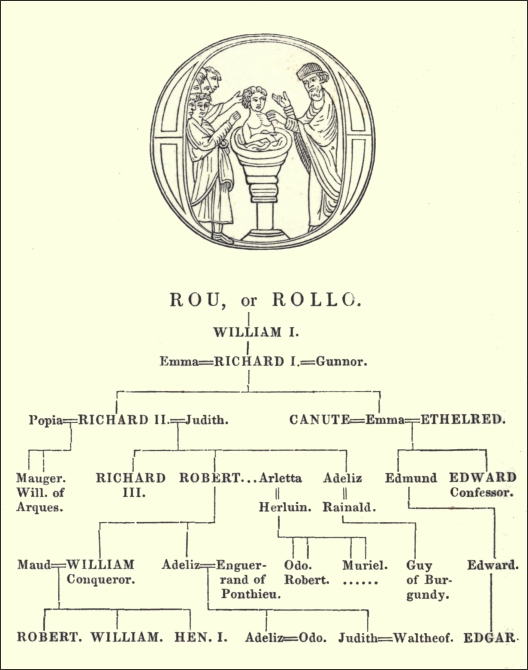

In honour of the second Henry, of the line of Roul, I have told the tale of Roul, of his noble parentage, of Normandy that he conquered, and the prowess that he showed. I have recounted the history of William Lunge-espee, till the Flemings killed him by felony and treason; of Richard his son, whom he left a child; [of the second Richard, who succeeded him; of his son the third Richard; who was soon followed by Duke Robert his brother, who went to Jerusalem, and died by poison; and now the tale will be of William his son, who was born to him of the 'meschine, Arlot of Faleise[9].']

HOW WILLIAM BECAME DUKE, AND HOW HIS BARONS REVOLTED AGAINST HIM.

The mourning for Duke Robert was great and lasted long; and William his son, who was yet very young, sorrowed much. The feuds against him were many, and his friends few; for he found that most were ill inclined towards him; those even whom his father held dear he found haughty and evil disposed. The barons warred upon each other; the strong oppressed the weak; and he could not prevent it, for he could not do justice upon them all. So they burned and pillaged the villages, and robbed and plundered the villains, injuring them in many ways.

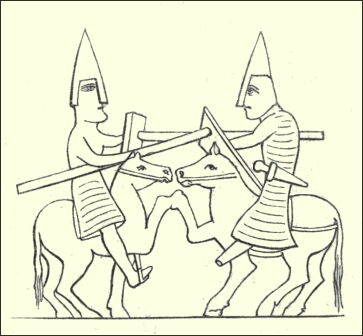

A mighty feud broke out between Walkelin de Ferrieres[10], and Hugh Lord of Montfort[11]; I know not which was right and which wrong; but they waged fierce war with each other, and were not to be reconciled; neither by bishop nor lord could peace or love be established between them. Both were good knights, bold and brave. Once upon a time they met, and the rage of each against the other was so great that they fought to the death. I know not which carried himself most gallantly, or who fell the first, but the issue of the affray was that Hugh was slain, and Walkelin fell also; both lost their lives in the same affray, and on the same day.

William meantime grew, and strengthened himself as his years advanced; yet still he was forced to hear and see many a deed which went against his heart, though he could do nothing to prevent it. The barons' feuds continued; they had no regard for him. Every one according to his means made castles and fortresses. On account of the castles wars arose, and destruction of the lands; great affrays and jealousies; maraudings and challengings; while the duke could give no redress[12] to those who suffered such wrongs.

Still as he advanced in age and stature he waxed strong; for he was prudent, and took care to strengthen himself on many sides. He had now held the land twelve years, when the country was involved in war, and suffered greatly through Neel de Costentin[13] and Renouf de Beessin, two viscounts of great power, who had the means of working much mischief.

William had about his person Gui, a son of Regnald the Burgundian[14], who had married Aeliz, the daughter of Duke Richard, and had two sons by her. Gui was brought up with William. When he was a young varlet, and first began to ride and to know how to feed and dress himself, he was taken into Normandy and brought up with William, who was very fond of him, and when he had made him a knight, gave him Briune[15] and Vernun, and other lands round about. When Gui had got possession, and had strengthened them till they had become good and fair castles, he became very envious of William, who had seigniory over him, and began to annoy him, and to challenge Normandy itself as his own right, reproaching William for his bastardy, and feloniously stirring up war against him; but it fell out ill for him, for in trying to seize all he lost the whole. He assembled and talked with Neel and Renouf, and Hamon-as-dens[16], and Grimoult del Plesseiz[17], who served William grudgingly. "There was not," he said, "any heir who had a better right to Normandy than himself. Richard was father to his mother; he was no bastard, but born in wedlock; and if right was done, Normandy would belong to him. If they would support him in his claim, he would divide it with them." So, at length, he said so much, and promised so largely, that they swore to support him according to their power in making war on William, and to seek his disherison by force or treason. Then they stored their castles, dug fosses, and erected barricades, William knowing nothing of their preparations.

He was at that time sojourning at Valognes, for his pleasure as well as on business; and had been engaged for several days hunting and shooting in the woods. One evening late his train had left his court, and all had gone to rest at the hostels where they lodged, except those who were of his housebold; and he himself was laid down. Whether he slept or not I do not know, but in the season of the first sleep, a fool named Golet[18] came, with a staff slung at his neck, crying out at the chamber door, and beating the wall with the staff; "Ovrez!" said he, "Ovrez! ovrez! ye are dead men: levez! levez! Where art thou laid, William? Wherefore dost thou sleep? If thou art found here thou wilt die; thy enemies are arming around; if they find thee here, thou wilt never quit the Cotentin, nor live till the morning!"

Then William was greatly alarmed; he rose up and stood as a man sorely dismayed. He asked no further news, for it seemed unlikely to bring him any good. He was in his breeches and shirt, and putting a cloak around his neck, he seized his horse quickly, and was soon on the road. I know not whether he even stopped to seek for his spurs, or whether he took any companion of his flight, but he hasted on till he came to the fords nearest at hand, which were those of Vire, and crossed them by night in great fear and anger. From thence he bent his way to the church of St. Clement[19], and prayed God heartily, if it were his will, to be his safe conduct, and let him pass in safety. He dared not turn towards Bayeux, for he knew not whom to trust, so he took the way which passes between Bayeux and the sea. And as he rode through Rie before the sun rose, Hubert de Rie[20] stood at his gate, between the church and his castle[21], and saw William pass in disorder, and that his horse was all in a sweat. "How is that you travel so, fair sire?" cried he. "Hubert," said William, "dare I tell you?" Then Hubert said, "Of a truth, most surely! say on boldly!" "I will have no secrets with you; my enemies follow seeking me, and menace my life. I know that they have sworn my death." Then Hubert led him into his hostel, and gave him his good horse, and called forth his three sons. "Fair sons," said he, "muntez! muntez! Behold your lord, conduct him till ye have lodged him in Falaise. This way ye shall pass, and that; it will be ill for you to touch upon any town." So Hubert taught them well the ways and turnings; and his sons understood all rightly, and followed his instructions exactly. They crossed all the country, passed Folpendant[22] at the ford, and lodged William in Falaise[Note 1]. If he were in bad plight, what matters so that he got safe?

Hubert remained standing on his bridge; he looked out over valley, and over hill, and listened anxiously for news, when they who were pursuing William came spurring by. They called him on one side, and conjured him with fair words to tell if he had seen the bastard, and whither and by what road he was gone. And he said to them, "He passed this way, and is not far off; you will have him soon; but wait, I will lead you myself, for I should like to give him the first blow. By my faith, I pledge you my word, that if I find him, I will strike him the first if I can." But Hubert only led them out of their way till he had no fear for William, who was gone by another route. So when he had talked to them enough of this thing and that, he returned back to his hostel.

The Cotentin and the Bessin were in great dismay that day, for the alarming news soon went through the country of William's being betrayed, and how he was to have been murdered by night. Some said he was killed; others that he was taken; many said that he had fled: "May God protect him," said all. Between Bayeux and the fords[23] the roads were to be seen covered with those who came from Valognes, holding themselves as dead or disgraced men, for having lost their lord, whom they had safe overnight. They know not where to seek their lord, who had been among them but last evening: they go enquiring tidings of him around, without knowing whither to repair. And heavily do they curse Grimoult del Plesseiz, and those who trust in him; for they vehemently suspect that he has done foul treason by his lord. Thus all Normandy was frightened and troubled at what had happened.

The viscounts hated the duke; they seized his lands, and omitted to lay hold of nothing which they could reach. They plundered him so completely, that he was unable to do any thing, either for right or wrong. He could not enter the Bessin, neither demand rent or service; so he went to France, to King Henry[24], whom his father Robert served, and complained against Neel, that he had injured him, and had seized his rents. He complained also of Hamon-as-dens, and of Guion le Burgenion; of Grimoult, who would have betrayed him, and whom he might well hate more than any other; and of Renouf de Briquesart, who took and spent his rents; and of the other barons of the country who had risen up against him.

HOW THE KING OF FRANCE CAME; AND OF THE BATTLE THAT WAS FOUGHT AT VAL DES DUNES.

The King of France, upon hearing the words that William spoke, and the complaints he made, sent forth and summoned his army, and came quickly into Normandy. And William called together the Cauchois, and the men of Roem, and of Roumoiz[25], and the people of Auge, and of the Lievin[26], and those of Evreux, and of the Evrecin. In Oismeiz also they quickly assembled when the summons reached them.

Between Argences and Mezodon[27], upon the river Lison[28], the men of France pitched their tents; and those of the Normans, who held fast to William, and came in his cause, made their camp near the river Meance, which runs by Argences[29].

When the Viscount of the Costentin, and the Viscount of the Bessin knew that William was coming, and was determined to fight, and had brought with him the King of France, in order to conquer them with his aid, they gave heed to evil counsel; and in the pride of their hearts, disdained to restore to him his own, or to seek peace or accept it. They sent for their people, their friends and relations, from all quarters; the vavassors and the barons, who were bound by oath to obey their commandment, were all sent for and summoned. They passed by various rivers and fords, and assembled at Valedune.

Valedune is in Oismeiz, between Argences and Cingueleiz[30]; about three leagues from Caen, according to my reckoning. The plain is long and broad, without either hill or valley of any size. It is near the ford of Berangier, and the land is without either wood or rock, but slopes towards the rising sun. A river bounds it towards the south and west.

At Saint Brigun de Valmerei[31], mass was sung before the king on the day of that battle, and the clerks were in great alarm. The French armed and arranged their troops at Valmerei, and then entered Valedune. There the communes[32] assembled well equipped, and occupied the river's bank. William advanced from Argences, and passing at the ford of Berangier, followed the river's course till he joined the French. His men were on the right, and the French on the left hand, with their faces towards the west, for their enemies came from that quarter.

Raol Tesson de Cingueleiz[33] saw the Normans and French advancing, and beheld William's force increasing. He stood on one side afar off, having six score knights and six in his troop; all with their lances raised, and trimmed with silk tokens[34]. The king and Duke William spoke together; each armed, and with helmet laced. They divided their troops, and arranged their order of battle, each holding in his hand a baston; and when the king saw Raol Tesson with his people standing far off from the others, he was unable to discover on whose side he was, or what he intended to do. "Sire," said William, "I believe those men will aid me; for the name of their lord is Raol Tesson, and he has no cause of quarrel or anger against me." Much was thereupon said and done, the whole of which I never heard; and Raol Tesson still stood hesitating whether he should hold with William.

On the one hand the viscounts besought him, and made him great promises; and he had before pledged himself, and sworn upon the saints at Bayeux, to smite William wherever he should find him. But all his men besought and advised him for his good, not to make war upon his lawful lord, whatever he did; nor to fail of his duty to him in any manner. They said William was his natural lord; that he could not deny being his man; that he should remember having done him homage before his father and his barons; and that the man who would fight against his lord had no right to fief or barony.

"That I cannot dispute," said Raol; "you say well, and we will do even so." So he spurred his horse forth from among the people with whom he stood, crying TUR AIE[35]; and ordering his men to rest where they were, went to speak with Duke William. He came spurring over the plain, and struck his lord with his glove, and said laughingly to him, "What I have sworn to do that I perform; I had sworn to smite you as soon as I should find you; and as I would not perjure myself, I have now struck you to acquit myself of my oath, and henceforth I will do you no further wrong or felony." Then the duke said, "Thanks to thee!" and Raol thereupon went on his way back to his men.

William passed along the plain, leading a great company of Normans, seeking the two viscounts, and calling out on the perjured men to stand forth. Those who knew them pointed them out on the other side among their people.

Then the troops were to be seen moving with their captains; and there was no rich man or baron there who had not by his side his gonfanon, or other enseigne, round which his men might rally; and cognizances or tokens, and shields painted in various guises[36]. There was great stir over the field; horses were to be seen curvetting, the pikes were raised, the lances brandished, and shields and helmets glistened. As they gallop, they cry their various war cries: those of France cry, MONTJOIE! the sound whereof is pleasant to them. William cries, DEX AIE! which is the signal of Normandy; and Renouf cries loudly, SAINT SEVER, SIRE SAINT SEVOIR[37]; and Dam as-denz goes crying Out, SAINT AMANT! SIRE SAINT AMANT[38]! Great clamour arose in their onset; all the earth quaked and trembled; knights were pricking along, some retiring, others coming up; the bold spurring forward, the cowards shrinking and trembling.

Against the King of France and the Frenchmen came up the body of the Costentinese; each party closing with the other, and clashing with levelled lances. When the lances broke and failed, then they assailed each other with swords. Hand to hand they fight, as champions in the lists, when two knights are matched; striking and beating each other down in many ways; wrestling and pushing and triumphing whenever any one yields. Each would be ashamed to flee, each tries to keep the field, each one boasts of his prowess with his fellow; Costentinese[39] and French thus contending with each other.

Great is the clamour and hard the strife; the swords are drawn, the lances clash. Many were the vassals to be seen there fighting, serjeants and knights overthrowing one another. The king himself was struck and beat down off his horse. A Norman whom no one knew had come up among them; he thought that if the king should fall, his army would soon be dispersed; so he struck at him 'de travers,' and overthrew him, and if his hauberk had not been very good, in my opinion he would have been killed. On this account the men of that country said, and yet say, jeering,

From Costentin came the lance

That struck down the King of France.[40]

and if their knight had got clear away, they might well pass with their jeer. But when he tried to go off, and his horse had begun its course, a knight came pricking, and hit him, striking him with such violence as to stretch him out at full length. And he soon fared still worse than even that; for as he recovered himself, and would have mounted his horse, and had laid his hand on the saddle bow, the throng increased around, and bore him from the saddle, throwing him down; and the horses trod him underfoot, so that they left him there for dead.

There was great press to raise the king up, and they soon remounted him. He had fallen among his men, and was no way hurt nor injured: so he arose up nimbly and boldly; never more so. As soon as he was on horseback, many were the vassals who were again to be seen striking with lance and sword; Frenchmen assaulting Normans, and Normans turning, dispersing, and moving off the field: and the king shewed himself every where in order to encourage his men, as he had been seen to fall. [Then Hamon-as-denz was beaten down, and I know not how many of his kindred with him, who never returned home thence, save as they might be borne home on their biers. Dan as-denz was a Norman, very powerful in his fief, and in his men. He was Lord of Thorigny, of Mezi[41], and of Croillie[42]. He had fought on all day, striking down the Frenchmen, and crying out SAINT AMANT! but a Frenchman marked him carrying himself thus proudly; so he stood still on one side, and watched him until he came near; and when he saw him turn and strike the king[43], the Frenchman charged forward with great force, and struck him gallantly, so that he fell upon his shield. I know not exactly how he was wounded, but only that he was carried away on his shield dead; and was borne thence to Esquai[44], and buried before the church. Many were the people who saw this feat done; how Hamon struck the king, and beat him off his horse, and how the French killed him for it, taking vengeance for their king.]

Raol Tesson stood by and looked on, till he saw the two hosts meeting, and the knights jousting; then he rode forward, and his course was easy to be marked. I know not how to recount his high deeds, nor how many he overthrew on that day.

Renouf the Viscount (I will not dwell long on the story) had with him a vassal named Harde[45], born and bred at Bayeux, who rode in the front of all, and gloried much in his prowess; William rushed against him, sword in hand, and aiming his blow aright, drove the trenchant steel into his body below the chin, between the throat and the chest, his armour not saving him. The body fell backward to the earth, and the soul passed away therefrom.

Renouf saw how the combat raged; he heard the clamour, the cry of war, and the clashing of lances; and he stood still, and was astounded, like one whose heart is faint. He feared much lest he were betrayed, and lest Neel had fled; and he was greatly afraid of William, and of the people who were with him. Evil betide him, he thought, if he were taken, and worse still would it he to be killed. He repented of having put on his armour, and was eager to get out of the battle; so he wandered in front and in rear, and at last, separating himself from his companions, determined to flee. Accordingly he threw away his lance and shield, and took to flight, running off with outstretched neck. Those about him who were cowards accompanied his flight, complaining much more than they had any occasion.

But Neel fought on gallantly; and if all had been like him, the French king would have come in an evil hour, for his men would have been discomfited and conquered. He was called on account of his valour and skill, his bravery and noble bearing, CHIEF DE FAUCON;—NOBLE CHIEF DE FAUCON was his title. He gave and received many a blow, and did all that lay in his power; but his strength began to fail; he saw that many of his men were lying dead, and that the French force increased on all sides, while the Normans fell away. Some fell wounded around him; some took fright and fled; and Neel at length quitted the field with more regret than he had ever before felt.

I will not tell, and in truth I do not know, (for I was not there to see, and I have not found it written) which of those present fought best; but this I know, that the king conquered, and that Renouf fled from the field. The crowd of fugitives was great, and the press of the pursuers was great also. Horses were to be seen running loose, and knights spurring across the plain. They sought to escape into the Bessin, but feared to cross the Osgne[46]. All fled in confusion between Alemaigne and Fontenai[47]; by fives, by sixes, and by threes, while the pursuers followed, pressing hard upon and destroying them. So many of them were driven into the Osgne, and killed or drowned there, as that the mills of Borbillon[48], they say, were stopped by the dead bodies.

And the king then gathered together his men, to return each into his own land. The sick and wounded were carried away, and the dead were buried in the cemeteries of the country.

William remained in his own land, and for a long while there was no more war. The barons came to accord with him, and paid such fines, and made him such fair promises, that he granted them peace, and acquittance of all their offences. But Neel could not come to an arrangement with him, and dare not stay in the land; so he remained long in Brittany before any accord was come to. Gui retreated from Valedune and fled to Brione; and William followed hard after him, and shut him up in a strong castle. In those days there was a fortress standing on an island of the river Risle[49], which surrounds the fortress and the mansion. And there, in Brione, Gui was shut up; but he had neither peace nor rest, and was in great bodily fear. The duke built up two castles near; so that provisions failing, and the besiegers pressing him hard, Gui surrendered up Brione and Vernun, when he could get no better terms. He might have remained with the duke, who would have provided for him; but he did not stay long; there was no friendship between them; so he went away to Burguine[50], to the country where he was born.

When the other Norman barons saw that the duke had obtained the upper hand of them all, they delivered hostages to keep the peace, and did fealty and homage to him. They obeyed him as their lord, and pulled down the new castles, and willingly or unwillingly rendered their service. He seized Grimoult del Plesseiz, and put him in prison at Rouen; and he had very good cause for so doing; for Grimoult would have murdered him traitorously, as we have said, at Valognes, had not Golet the fool given him warning. Grimoult confessed the felony, and accused of fellowship in it a knight called Salle[51], who had Huon for his father. Salle offered to defend himself from the charge, and a single combat was thereupon arranged between them; but when the appointed day came, Grimoult was found dead in the prison. It occasioned great talk; and he was buried, chained as he was, with the irons on his legs. At Bayeux, when the church was dedicated, part of Grimoult's lands was granted to Our Lady the Blessed Mary; and part divided in the abbey, to each his share.[52]

HOW CANUTE DIED, AND ALFRED FELL BY TREASON; AND HOW EDWARD AFTERWARDS BECAME KING.

He who made the history of the Normans, tells us that in those days[53] Kenut, who was father of Hardekenut, and had married Emma, the wife of Alred[54], the mother of Edward and of Alfred, died at Winchester. Hardekenut, during the lifetime of his father, by the advice of his mother Emma, had gone to Denmark, and became king there, and was much honoured. On account of Hardekenut's absence, and by an understanding with her, England fell to Herout[55], a bastard son of Kenut.

Edward and Alfred heard of Kenut's death, and were much rejoiced; for they expected to have the kingdom, seeing that they were the nearest heirs. So they provided knights and ships, and equipped their fleet; and Edward, having sailed from Barbeflo[56], with forty ships, soon arrived at the port of Hantone, hoping to win the land. But the Englishmen, who were aware that the brothers were coming, would not receive them, nor suffer them to abide in the country. Whether it was that they feared Herout the son of Kenut, or that they liked him best; at any rate they defended the country against Edward; and the Normans on the other hand fought them, taking and killing many, and seizing several of their ships. But the English force increased; men hastened up from all sides, and Edward saw that he could not win his inheritance without a great loss.He beheld the enemy's force fast growing in numbers, and that he should only sacrifice his own men; so fearing that, if taken, he himself might be killed without ransom, he ordered all his people to return to the ships, and took on board the harness. He could do no more this time, so he made his retreat to Barbeflo.

Alfred meantime sailed with a great navy from Wincant[57]; and arriving safely at Dovre, proceeded thence into Kent. Against him came the earl Godwin[58], who was a man of a very low origin. His wife was born in Denmark, and well related among the Danes, and he had Heraut, Guert, and Tosti for his sons. On account of these children, who thus came by a Dane, and were beloved by their countrymen, Godwin loved the Danes, much better in fact than he did the English.

Hearken to the devilry that was now played; to the great treason and felony that were committed! Godwin was a traitor, and he did foul treason; a Judas did he show himself, deceiving and betraying the son of his natural lord,—the heir to the honor (lordship),—even as Judas sold our Lord. He had saluted and kissed him; he had eaten too out of his dish, and had pledged himself to bear faith and loyalty. But at midnight, when Alfred had laid down to rest and slept, Godwin surprised and bound him; and sent him to London to king Herout, who expected him, knowing of the treason.From thence he sent him to Eli, and there put out his eyes and murdered him dishonourably, and by treachery which he dared not to avow. Those too who came with Alfred (hearken to the foul cruelty!) were bound fast and guarded; and taken to Gedefort[59], where all, except every tenth man, lost their heads and died miserably. When the English had numbered them, setting them in rows, they then decimated them, making every tenth man stand on one side, and striking off the heads of the other nine; and when the tithe so set apart amounted to a considerable number, it was again decimated, and all that was at last saved was this second tithe.

Herout soon after died, and went the way he deserved; whereupon the men of England assembled to consider about making a king in his place. They feared Edward who was the right heir, on account of the decimation of the Normans, and the murder of his brother Alvred; and at last they agreed to make Hardekenut king of England. So they sent for Hardekenut, the son of Emma and Kenut, and he repaired thither from Denmark, and the clergy crowned him: but he sent for Edward his brother, the son of Emma his mother, and kept him in great honour at his court, and was king over him only in name. Hardekenut was king twelve years, and then fell ill. He did not languish long, but soon died. His mother lamented over him exceedingly; but it was a great comfort to her that her son Edward was come; and he obtained the kingdom[60], the English finding no other heir who was entitled to the crown.

Edward was gentle and courteous, and established peace and good laws. He took to wife Godwin's daughter, Edif[61] by name. She was a fair lady, but they had no children between them, and people said that he never consorted with her; but no man saw that there was ever any disagreement between them[62]. He loved the Normans very much, and held them dear, keeping them on familiar terms about him; and loved duke William as a brother or child. Thus peace lasted, and long will last, never I hope to have an end.[63]

THE REVOLT OF WILLIAM OF ARQUES; AND HOW HE AND THE KING OF FRANCE WERE FOILED BY DUKE WILLIAM.

William of Arches was a brave and gallant knight[64], brother to the archbishop Maugier, who loved him well. He was also brother on one side to duke Robert, being the son of Richard and Papie, and uncle of William the bastard. He was versed in many a trick and subtlety, and plotted mischief against the duke, claiming a right of inheritance, inasmuch as he was born in wedlock. On account of his relationship, and to secure his fealty, the duke had given him, as a fief, Arches and Taillou[65]; and he received them and became the duke's man; promising fealty, though he observed it but for a very brief space of time. To enable him the better to work mischief to his lord, he built a tower above Arches, setting it on the top of the hill[66], with a deep trench around on every side. Then confiding in the strength of his castle, and in his birth in wedlock, and knowing that the king of France had promised to succour him in case of need, he told William he should hold his castle free from all service to him; that he was in wrongful possession of Normandy, being a bastard and without any title of right.

But the duke had now great power; for he was very prudent, and no man is weak who possesses wisdom. He sent for William of Arches, and summoned him to attend, and do his service: but he altogether refused, and defied the bastard, relying on aid from the king of France. He plundered the country round of provisions and stores of every sort, heeding little whence it came, and thus supplied his castle and tower.

The duke bore with this behaviour but a very little while, and without further 'parlement' sent for his people from all sides. Then with ditches and stakes and palisades he quickly formed a fort[67], at the foot of the hill in the valley, so as to command all the country round, and prevent those in the castle from obtaining either ox, or cow, or calf: and the fort was so strong, and was garrisoned by so many knights, the best of the chivalry of all Normandy, that no effort of either king or earl to take it, was likely to be of any avail. So the duke, having thus completed his work, went his way to attend to his affairs elsewhere.

The king of France soon knew that the duke had fortified his post, and blockaded the tower, so that no provisions could enter therein. Then he assembled a great chivalry, and got together much store of provisions and arms, intending to relieve the tower of Arches, where the supply of corn began to fail. Having reached Saint-Albin[68], with an ample store both of corn and wine, the king made a halt, ordering sumpter horses to be made ready to carry the stores onward, and providing a troop of knights to form the convoy.

Those in the besiegers' fort soon heard of the great preparations waiting at Saint-Albin to provision and relieve Arches. Then they selected their strongest and best fighting men, and privily formed an ambuscade in the direction of Saint-Albin. Having done this, they sent out another party with orders to charge the king's force, and then to turn back, making as if they would flee. But when they had passed the spot where the ambuscade lay, they turned quickly round on those who were pursuing, and fiercely attacked the French; those also who were lying in ambuscade riding forth, and joining in the assault.

The Frenchmen were thus grievously taken in; and being separated from the rest of their army, the Normans charged them boldly, and took and killed many. Hue Bardous[69] was taken early in the affray; Engerrens count of Abevile[70], was killed, and all suffered greatly. The king of France was in great grief; he mourned heavily, and was sorely vexed for the knights that had been thus surprised, and for his brave barons who had fallen. He made ready the baggage horses, and carried the stores to the town of Arches[Note 2]; and when he had so done, he returned back to Saint-Denis with no small shame and disgrace, as it seems to me.

The duke was sojourning at Valognes, for the sake of the woods and rivers which abound there, and on other affairs and business of his own, when a messenger came spurring on with pressing speed, and hastening unto him, cried out and said, "Better would it be for thee to be elsewhere! they who guard the frontiers have need of thy aid; for thy uncle William of Arches hath linked himself by oath and affiance to king Henry of France. The king hasteth to relieve and store Arches, and William will do him service for it in return."

Then the duke tarried not till the varlet should speak further, nor indeed till he had well said his say; but called for his good horse. "Now I shall see," said he, "who of you is ready, now I shall see who will follow me." And he made no other preparation, but forthwith crossed the fords[71], passed Baieues and then Caen, and feigned as though he would go to Rouen. But when he came to Punt-Audumer, he crossed over to Chaudebec, and from Chaudebec rode on to Bans-le-Cunte. What need of many words? He halted and galloped on till he joined his people before Arches; but none of those who took horse at the same time at Valognes kept up with him; and all wondered how he had come so soon from such a distance, when no one else had been able to do as much[72].

Then he rejoiced greatly to learn what had happened; how the French had been discomfited, and their people routed and taken prisoners. William of Arches however kept close, defending his castle bravely and long; and he would have held it longer still, had not provisions failed him. So at length he abandoned land, and castle, and tower; and surrendering all up to duke William, fled to the king of France.

HOW THE KING OF FRANCE INVADED NORMANDY, AND WAS BEATEN AT MORTEMER.

The French had often insulted the Normans by injurious deeds and words, on account of the great dislike and jealousy which they bore to Normandy. They continually spoke scornfully, and called the Normans BIGOZ and DRASCHIERS[73]; and often remonstrated with their king, and said, "Sire, why do you not chase the Bigoz out of the country? Their ancestors were robbers, who came by sea, and stole the land from our forefathers and us." By the persuasion of these felons, who talked thus because they hated the duke, the king undertook the enterprise[74]; though it was disliked by many of his men. He said he would go into Normandy, and would conquer it; he would divide his army into two parts, and invade in two directions. And what he said, he endeavoured to execute; summoning his people from all sides.

He collected them in two positions, according as the river Seine divided them; those of Reins and those of Seissons, of Leun[75], and of Noions; those of Melant[76], and of Vermandeiz; of Pontif[77] and of Amineiz; those of Flanders and of Belmont[78]; of Brie and of Provens. All these, who are beyond Seine he assembled by twenties, by hundreds, and by thousands, in Belveisin, meaning to enter the pays de Caux from that side. To the Conestable and Guion[79], he sent his brother Odo[80], and directed them to enter by Caux, and ravage all the land around.

And he summoned all the rest of his people, according as the river Seine divides them from the others, to meet him at Meante[81]; those of Toroigne and of Bleis; of Orlianz and of Vastineis; of the Perche and of the Chartrain; of the bocage and of the plain; those of Boorges[82], of Berri; of Estampes and of Montlheri; of Grez and of Chasteillun; of Senz and of Chastel-Landun, the king ordered to come to Meante. And he menaced the Normans, and boasted much that he would destroy Evrecin, Rosmeis, and Lievin[83], and would ride even as far as the sea, returning by Auge.

William was in great alarm, for he was much afraid of the king's power; and he also formed his men into two companies. About Caux, he placed Galtier Gifart[84], and the men of that country; Robert, count d'Ou, and old Huon de Gornai; and with these he ranged William Crespin[85], who had much land in Velquessin[86]. These had under them the people of the country around them, their relations and friends. The duke retained the other company under his own command, to oppose the king. He assembled the men of the Beessin, and the barons of the Costentin, and those of the valley of Moretoing[87]; and of Avranehes, which is beyond it; Raol Tesson of Cingueleis, and the knights of Auge and of Wismeis[88]; all these the duke summoned to meet him. He would, he said, be close upon the king, and encamp hard by him, looking keenly after the foragers, that they should not stray far without having some damage, if he could help it; and he caused all provisions to be removed from the way by which the king must pass; and drove the beasts into the woods, and made the villains keep watch over them there.

The barons who were stationed in Caux, to defend that part of the country, kept themselves to the woods and forests till the people of the country could be got together; and passed from wood to wood, concealing themselves in the thickets. But the men of France marched on, and encamped at Mortemer. They remained there one night for the convenience of the hostels; expecting that they could roam as they pleased over the whole country, without meeting any knights who would dare to encounter, or bear arms against them; for they believed that all the Norman knights were gone towards Evreues with their lord, and that he had retreated thither from fear of the king.

The Frenchmen demeaned themselves insolently, and with great cruelty. Wherever they had passed, they destroyed all they found, ravaging the villages and manors, burning houses, and plundering them of the furniture; seizing the villains, violating the women, and keeping whatever they pleased; till they had come to Mortemer, where they found fair quarters in the hostels. By day they delivered the country up to pillage, and devoted the night to revelry, searching out the wine and killing the cattle, eating and drinking their fill.

The Normans knew well from their spies where the French lay, and what their plans were; so they assembled their men together during the night, summoning their friends and companions; and in the morning before day-break, while the French were yet sleeping, behold! they surrounded Mortemer, and set fire to the town. The flames spread from one hostel to another, till the fire raged through all the streets. Then the Frenchmen were to be seen in consternation: the whole town was in confusion, and the melee became fierce; they rushed from the hostels, seizing such arms as they could find, and were grievously discomfited, for the Normans stopt them at the barriers. One man endeavours to mount his horse, but cannot find the bridle; and another would quit his hostel, but is unable to reach the door. The Normans guard all the issues, and the heads of the streets; and there the encounters are rudest, and the feats of arms the fairest.

From the rising of the morning's sun, till three in the afternoon, the assault lasted in its full force, and the battle continued to be hot and fierce. The French could not escape, for the Normans would let no one pass. The first who quitted the field and fled was Odes; and the Normans took Guion, the count of Pontif, alive and in arms; but they killed Valeran his brother, a very brave and valiant knight. There was no varlet, let him be ever so mean, or of ever so low degree, but took some Frenchman prisoner, and seized two or three horses with all their harness; nor was there a prison in all Normandy, which was not full of Frenchmen. They were to be seen fleeing around, skulking in the woods and bushes; and the dead and wounded lay amidst the burning ruins, and upon the dung-hills, about the fields, and in the by-paths.

That same night, the news passed quickly to where the duke lay with his army; how that the French were discomfited, and the invasion stayed. News travels fast, and is swift; and whoso bears good tidings may safely knock at the gate[89]. The duke rejoiced greatly at the discomfiture of his enemies; and he sent a man, whether varlet or esquire I know not, to the place where the king was encamped, and had retired to his bed. He ordered the man to climb up into a tree, and all night to cry aloud, "Frenchmen, Frenchmen, arise! arise! make ready for your flight, ye sleep too long! Go forth at once to bury your friends, who lie dead at Mortemer[90]."

As the king heard the cry, he marvelled much, and was sorely dismayed. So he sent out for his friends, and besought and conjured them to tell him if they had heard any such tidings as the man proclaimed from the tree. And whilst they yet talked and conversed with the king, concerning what had happened, behold the news came and spread all around, how that the best of their friends lay dead at Mortemer, and how they who had escaped alive were made captive, and were in chains and in prison in Normandy.

The French were greatly moved and troubled at the news, and went crying out that they tarried too long. They seized the palfreys and war-horses, harnessed and loaded the baggage horses, set fire to the tents and huts, emptied them of every thing, and sent all on forward; and the king went off on his way homeward, looking cautiously around him. Had the duke wished to pursue, he might have injured him much, but he did not desire to annoy him more. "He has had quite enough," said he, "to trouble and cross him;" and he would not add more to his annoyance.

The king returned to Paris, the barons to their homes, and the great people whom he had led forth returned to their own countries. But his wrath against the Normans was very great, on account of those whom they had taken prisoners, and still more for those who were killed. The dead he could not recover, but he wished to redeem those who were prisoners; so he sent word to the duke, that if he would release his prisoners, he would make truce and peace with him till other cause of difference should arise; and that whatever the duke had taken or might take from Giffrei Martel, should never be a cause of war between them, or be alleged as a grievance against him.

And thereupon accordingly was done as I tell you; the duke restored the Frenchmen who were prisoners, but the harness was left to those who had won it; and the prisoners repaid to their captors the charges they had occasioned to them.

HOW THE KING OF FRANCE CAME AGAIN AGAINST DUKE WILLIAM, AND WAS DEFEATED AT VARAVILLE.

Duke William carried himself gallantly, and triumphed over all his enemies; he was loved for his liberality, and feared for his bravery. He conquered many and won over many, lavishing his gifts around, and spending much; till the French became very jealous of his chivalry; of the troops that he had, and of the lands he conquered. Their king could never be reconciled to the Normans; but said that he would sooner perjure himself, than not have his revenge for the battle of Mortemer.

Then under the advice of Giffrei Martel[91], before August, when the corn was on the ground, he summoned together all his barons, and the knights who held fiefs of him, and owed him service, and entered Normandy, passing by Oismes[92], which they assaulted without tarrying before it long. From thence they traversed all Oismes, and through the Beessin as far as the sea coast; burning the villages and bourgs; and ruining and plundering both men and women, till at length they came to St. Pierre-sor-Dive. The town was completely garrisoned by them, and the king lay at the abbey[93].

The duke was with his people at Faleise, when the news came, concerning the wrong the king was doing him; and it grieved him sorely. So he sent out and assembled his knights, and strengthened his castles, cleansing the fosses, and repairing the walls; being determined to let the open country be laid waste, if he could maintain his strong places. He could easily, he said, recover the open lands, and repair the injury done to them. So he did not shew himself at all to the French, but let them wander over the country, intending to give them scurvy usage on their return back from their expedition.

The king meantime went on with his project. He would go, he said, towards Bayeux, and ravage the whole of the Beessin, and on his return thence would pass by Varavile[94], and lay waste Auge and Lievin. Accordingly the French overran the Beessin, as far as the river Seule[95]; and returned from thence to Caen, where they passed the Ogne[96]. Caen was then without a castle, and had neither wall nor fence to protect it[97]. When the king left Caen, he proceeded homeward by Varavile, as he had proposed.

His train was great and long, so that it could not all be kept together; and the press was great to pass the bridge, every one wanting to be the foremost.

The duke, knowing some how or another all that was going on, and by what route the king would pass, hastened upon his track with the great body of troops that he led, and conducted his people in close order along the valley below Bavent[98]. All over the country he sent out word, and summoned the villains to come to his aid as quickly as they could, with whatever arms they could get. Then from all round the villains were to be seen flocking in, with pikes and clubs in their hands.

The king had passed the river Dive, which runs through that country, together with all those of his host who had taken care to move quickly forward. But the baggage train was altogether, and far behind, extending over a great length. The duke, seeing that all who were thus in the rear were certain to fall into his hands, pressed on his men from village to village; and when he reached Varavile, he found those of the French there who remained to form the rear guard. Then began a fierce melee, and many a stroke of lance and sword. The knights struck with their lances, the archers shot from their bows, and the villains attacked with their pikes; charging and driving them along the chaussee, overwhelming and bearing down numbers. The Normans kept continually increasing in numbers, till they became a great force, and the French pressed forwards, one pushing the other on. The chaussee incommoded them very much, being long and in bad repair, and they were encumbered by their plunder. Many were to be seen breaking the line, and getting out of the track, who could not retrace their steps, nor reach the main road again.

The great press was at the bridge, every one being eager to reach it. But the bridge was old, the boards bent under the throng, the water rose[Note 3], and the stream was strong; the weight was heavy, the bridge shook and at length fell, and all who were upon it perished. Many fell in close by the bridge foot where the water was deep; all about harness was to be seen floating, and men plunging and sinking; and none had any chance of life save skilful swimmers.

The cry arose that the bridge was broken. Grievous and fearful was that cry, and no one was so brave or bold as not to tremble for his life when he heard what had happened, and to see that his hour of exultation was gone by. They see the Normans meanwhile pressing on from behind, but there was no escape; they go along the banks of the river, seeking for fords and crossings, throwing away their arms and plunder, and cursing their having brought so much. They go straggling and stumbling over the ditches, helping each other forward, the Normans pursuing and sparing no one, till all those who had not crossed the bridge were either taken prisoners, killed, or drowned. Never, they say, were so many prisoners taken, or such great slaughter made in all Normandy. And William glorified God for his success.

The river and the sea also swept away numbers, the king looking on in sorrow and dismay. From the height of Basteborc, he looked down and saw Varavile and Caborc; he beheld the marshes and the valleys, which lay long and broad before him, the wide stream, and the broken bridge; he gazed upon his numerous troops thus fallen into trouble; some he saw seized and bound, others struggling in the deep waters; and to those who were drowning he could bring no succour, neither could he rescue the prisoners. In sorrow and indignation he groaned and sighed, and could say nothing; all his limbs trembled, and his face burned with rage. Willingly, he cried, would he turn back, and endeavour to find a passage, if his barons would so counsel, but no one would give such advice. "Sire," said they, "you shall not go; you shall return another time and destroy all the land, taking captive all their richest men."

Then the king went back into France, full of rage and heaviness of heart, and never after bore shield or lance; whether as a penance or not I know not. He never again entered Normandy: nor did he live long, but did as all men must do; from dust became, to dust he returned. At his death he was greatly lamented, and his eldest son Philip[99] was crowned king in his stead.

HOW WILLIAM PROSPERED, AND HOW HE WENT TO ENGLAND TO VISIT KING EDWARD; AND WHO GODWIN WAS.

THE story will be long ere it close, how William became a king, what honour he reached, and who held his lands after him. His acts, his sayings and adventures that we find written, are all worthy to be recounted; but we cannot tell the whole. In his land he set good laws; he maintained justice and peace firmly, wherever he could, for the poor people's sake, and he never loved the knave nor the company of the felon.

By advice of his baronage he took a wife[100] of high lineage in Flanders, the daughter of count Baldwin, and the granddaughter of Robert king of France, being the daughter of his daughter Constance. Her name was Mahelt[101], related to many a noble man, and very fair and graceful. The count gave her joyfully, with very rich appareillement, and brought her to the castle of Ou[102], where the duke espoused her. From thence he took her to Roem, where she was greatly served and honoured.

At Caem the duke built two abbeys, endowing them richly. In the one, which was called Saint Stephen, he placed monks; Mahelt his wife took charge of the other, which is that of The Holy Trinity; she placed nuns there, and was buried in it as she had directed in her life, from the love which she had always used to bear towards it[103].

And the duke did what, I believe, no one before or after did. He sent[104] for all his bishops to assemble, with his earls, abbots, and priors, barons and rich vavassors, at Caem, there to hear his commandment; and caused the holy bodies, wherever he could find them, to be brought thither, whether from bishopric or abbey, over which he had seigniory. He had the body of St. Oain[105] taken from Roem to Caem in a chest; and when the clergy, and the holy relics, and the barons, of whom there were many, were assembled on the appointed day, he made all swear on the relics to hold peace and maintain it from sunset on Wednesday to sunrise on Monday. This was called 'The Truce', and the like of it I believe is not in any country. If any man should beat another meantime, or do him any mischief, or take any of his goods, he was to be excommunicated, and amerced nine livres to the bishop. This the duke established, and swore aloud to observe, and all the barons did the same; they swore to keep the peace and maintain the truce faithfully.

To commemorate this peace through all time, that it might endure for ever, they forthwith built a minater of hewed stone[106] and mortar, on the spot where they swore upon the relics which had been brought to the council. Many who had assisted at founding the minster called it Toz-sainz[107], on account of so many holy relics having been there; but it pleased many men to call it Sainte-paiz, on account of the peace sworn to when it was built: at least I have heard it called both Sainte-paiz and Toz-sainz. Close by they built a chapel called Saint-Oain's, on the spot where his bones had rested while the council sat.

William was generous, and the strangers who knew him, cherished him much. He was very gentle and courteous, therefore king Edward loved him well; great indeed was their love, each holding the other his lord. The duke went to see Edward and know his mind; and having crossed over into England[108], Edward received him with great honour, and gave him many dogs and birds, and whatever other good and fair gifts he could find, that became a man of high degree. He did not tarry, but returned into Normandy; for he was engaged with the Bretons, who were at that time disturbing him.